Blog

Set it and forget it

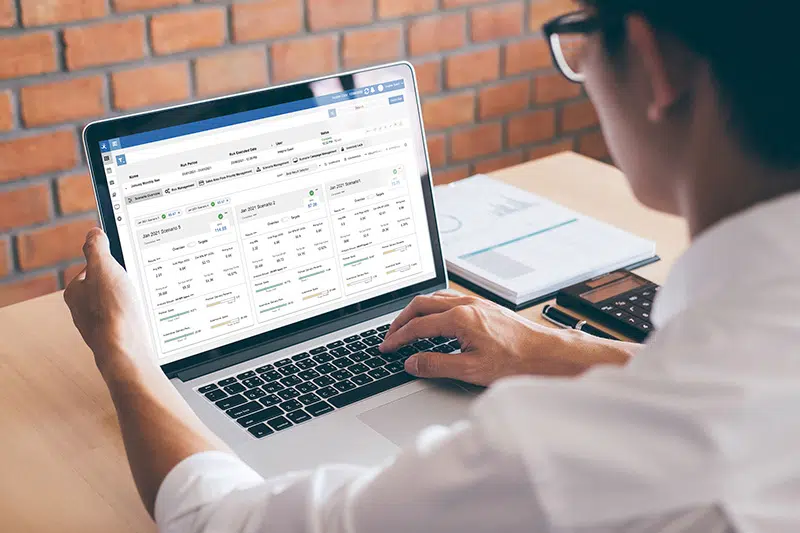

As your linear TV revenue continues to decline, you’ll need to streamline workflows to reduce costs, while meeting delivery requirements more efficiently. With GamePlan™, you can increase profitability by automating the complex process of spot placement for audience-based campaigns, while ensuring your ad inventory is utilized to its full potential.

Benefits

Reduce the burden and cost of manual spot placement for non-premium inventory. Use your inventory more strategically by automatically adjusting to viewership levels to meet delivery commitments.

Increase revenue through optimization

Free up inventory while still hitting audience commitments to increase revenue by up to 20 percent.

Reduce operational costs through automation

Streamline ad workflows to improve operational efficiency by up to 80 percent.

Enable hybrid flexibility

Manually place spots in premium inventory and automate optimized placement of everything else.

Eliminate time-consuming makegoods

Meet your audience delivery commitments every time without manually placing spots.

Create a pathway to cross-platform selling

Target a specific demographic and volume of impressions across linear and digital.

Utilize open APIs

Easily integrate with existing scheduling and traffic systems.

Maximize profits with automated, audience-based ad trading.

Discover a more efficient and flexible way to trade non-premium linear ad inventory.

Solving your toughest ad management problems

In today’s dynamic media landscape, where streaming TV continues to reshape the industry, staying competitive while delivering high-quality content to your audience has never been more crucial. The key to success lies in harnessing every monetization opportunity efficiently.

Hybrid operation

Manually place spots in premium inventory while automating optimized placement in non-premium inventory.

Inventory optimization

Automatically react to real-world data to optimize and re-optimize your inventory on a daily basis.

Holistic optimization

Make more informed decisions when all inventory supply and demand is taken into account, instead of on a per-campaign basis.

Features

Powerful tools

Inefficient Spot Removal: Cleans up spots that are no longer optimally placed

Right Sizer: Removes spots that are contributing to an order’s potential overdelivery

AutoPilot: Generates alternative scenarios at the click of a button

Best Results Selector: Automatically scores each scenario according to predefined criteria

Superior capabilities

Parallel optimizations allow operators to experiment with “what-if” scenarios

Advanced optimization algorithm automates the complex process of spot placement on a daily basis

Meet audience commitments using the least amount of inventory with efficiency-based algorithms

Place 30,000 spots per minute

Unmatched integration

Wrapped in APIs fully documented in SwaggerHub

Our technology partners

Imagine Communications partners with some of the industry’s most innovative companies to develop open-standard solutions that enable you to simplify your business operations, resolve workflow challenges and capitalize on emerging market opportunities.

Related products

Powerful alone, exceptional together

Increase efficiency and reduce workload by integrating business systems.

Traffic

Landmark™ Sales

Traffic

xG Linear™

Traffic

OSI™ Traffic & Billing

Related services

Services

Maximize your return on investment and minimize risk with Imagine’s full range of services to support, manage, guide, and optimize your applications and infrastructure. Our unique processes, tools, and methods ensure your business success.

Consulting

Professional Services

Managed Services

Customer Care

Latest insights

Insights and resources

From Chaos to Clarity: How Total TV Aligns Sales, Ops, and Strategy

Blog

Automating TV Advertising: Cutting Costs and Streamlining Sales

Blog

Revolutionizing TV ad sales: How audience-based trading unlocks untapped revenue

Ready to increase the profitability of your linear TV service?

Contact our experts today to get started.